Several clients have been discussing with us the issues of inflation and then interest rates and how it affects them.

Their primary issue is:

How does it affect my day to day expenses (called “Cost of Living”).

If you haven’t heard it yet, you will undoubtedly hear it soon, as this is already one major topic of discussion at the moment, with both sides of politics in the blame game for who will be the next PM!

You will see both sides blame each other for the increase in inflation, and then somehow that one side of politics or the other has been responsible for:

- COVID – and the current delays in receiving cars, or building materials, or computer chips etc.; and

- Oil prices – which have been driven by one Mr Vladimir Putin.

It would be great if any mere mortal could control the above items…

There is a lot currently going on around the world and many events over the last 18 to 24 months. To give some context, we thought we would help clients with a bit more background and assistance on how this could affect you, your family, your income, and your business.

A quick history lesson over the last 24 months

- The COVID outbreak causes the pandemic, and some countries to enter a technical recession. Australia avoided recession.

- Stimulus packages around the world to deal with not just the health issues and items (like vaccines, and hand sanitiser and masks) but also to get people spending money and provide assistance for those who have lost their jobs or had to take pay reductions.

- Labour shortages in Australia (and in the first world countries), as the closing of borders, affected labour flow into the country.

- Bringing jobs back onshore – we have seen several big businesses bring their call centres and support centres back onshore, as they experienced places like India and Vietnam (which are prominent outsourcing places) unable to work from home. The staff that was helping at a call centre could not work from home at their house in India (for example) due to poor internet and computer infrastructure. As such, businesses such as Telstra and the Big 4 Banks could not rely on their service centres to operate effectively. That has created more jobs in Australia with fewer people to do them.

-

Materials shortages globally – the scarcity in materials has been caused by a range of factors, including countries such as Brazil (which export a lot of iron ore and coal, like Australia) not being able to operate due to being ravaged by COVID.

-

With more people in Australia at home and not being able to travel or get out and do things, we saw the most significant savings for more than 30 years throughout the pandemic. Some analysts even think that the savings have been since the 1970s.

-

An effective war on Ukraine was declared by Russia (even though Putin is still saying that it is not a war), which has affected a range of factors, including but not limited to Oil, Energy, agriculture and other exports that Ukraine provides.

What about property and Investments?

With the pandemic, many so-called experts were saying that property, particularly in Australia, was going to go down by 40%. Property has, in fact, gone up.

Many people are now saying that the property market is overheated, but we don’t think that either.

Property has increased, no doubt about that, but if you review a property that you paid for, say in 2002, it spiked up leading up to the GFC to peak in around 2007. Then, it dropped down a lot from 2007 to around 2013. Then, it went up a bit in 2014, before slumping again in 2016 and 2017. So, now we are in 2021 and 2022, and the property market has increased. Many people have only just seen property they bought in 2006 or 2007 go back to the price they paid for it. In our view, that can hardly be called a Boom!

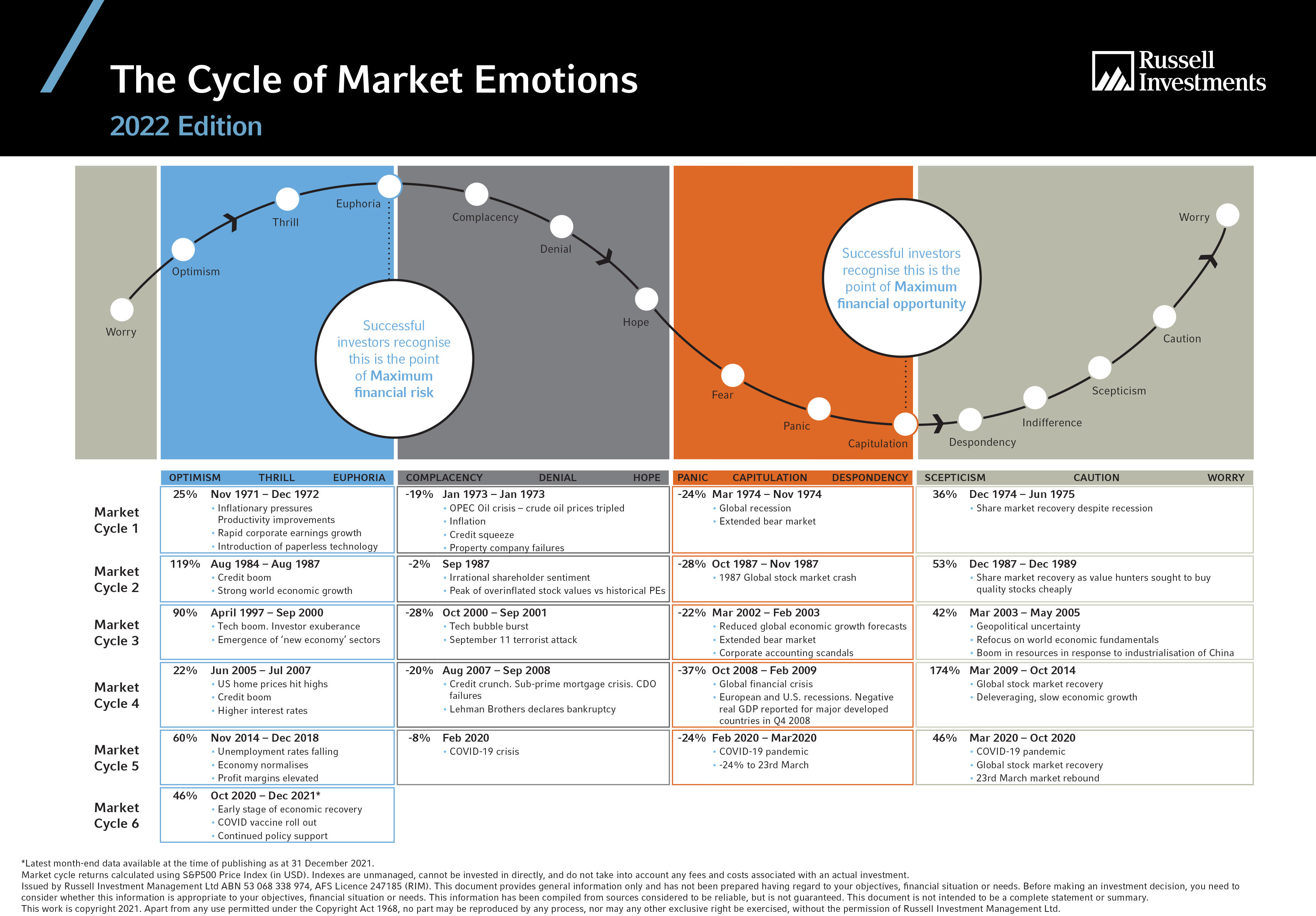

With that as a background, we provide a few things for you to review and consider – including the usual investment psyche and the cycle of emotions, plus some questions and answers on inflation and interest rates, that we thought were very timely and written in more understandable terms.

Outside the usual “cost of living” that both inflation and interest rates affect, the two significant issues that inflation and interest rates affect are:

a) Investors – as inflation and interest rates affect profits and, therefore, dividends. It can impact different investments and businesses in different ways.

For most clients who are relying on their investments for dividend income, it may positively affect them in that interest rates may go up (albeit slightly); therefore, better income returns. Or they may affect profits, which brings profits down and, thus, dividends down.

b) Borrowers – as the cost of finance now increases. Many clients have home loans or business loans and have been asking about fixing rates or not fixing rates.

For investors, the current climate brings uncertainty. Some economists and analysts believe that the current situation is similar to the Iraq / Kuwait war that was in 1990. That war helped the US and the global economy out of the recession after the 1987 stock market crash. Other economists are of the view that this could be similar to a GFC, with high demand for renovation and homebuilding.

Our usual approach is to sit somewhere in between.

Interestingly, in the Cycle of Market Emotions poster from Russell Investments. the Iraq / Kuwait War in 1990 did not make it as “a world event” that caused emotion! (Click the poster for a better view)

Note:

For borrowers, interest rates are typically not dictated by the Reserve Bank and its interest rate movements. Instead, various banks set interest rates based on the supply and demand of money.

For more on this and also how the Interest rate affects the stock market, see this article.

Questions & Answers extracted from the CBA

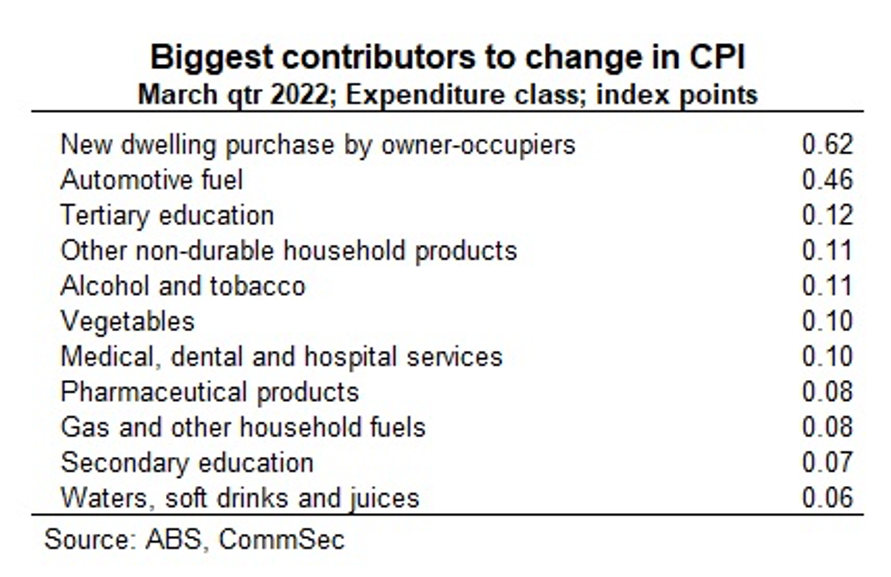

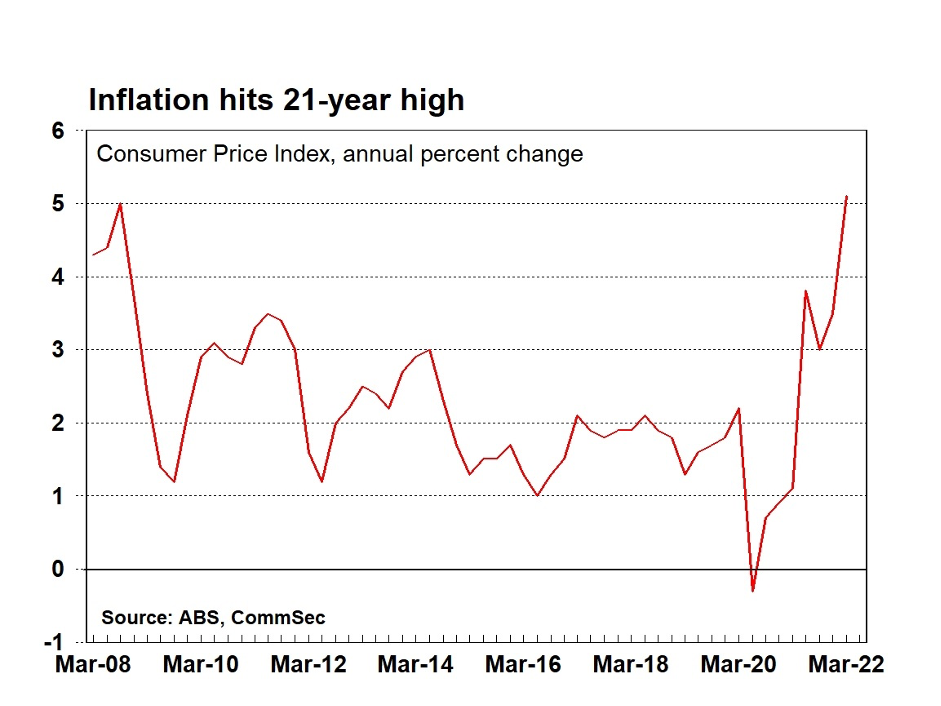

At 5.1 per cent, inflation is running at the fastest annual rate in 21 years.

Why has this occurred and what does it mean for interest rate settings?

Why is the inflation rate so high?

A lot has to do with global factors – Covid and the war in Ukraine. In the March quarter, fuel prices rose by 11 per cent, to be up 35.1 per cent on the year. The annual lift in fuel prices was the biggest since the 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Across the globe, oil production is not keeping up with demand, causing oil supplies to soar. Indeed, the impact hasn’t just been at the petrol pump; rising transport costs have boosted prices for a raft of items like food.

But apart from higher oil prices, what are some of the other factors driving inflation?

- Well, as noted, there is COVID. Across the globe, people have contracted the virus and have had to stay away from work. Demand for goods has gone up, but there are not enough goods to meet the higher demand, pushing up prices. That is also shown in the cost of housing here in Australia. More people want to build, but there are not enough builders and building materials to go around.

- Then there are other factors like the recent floods in NSW and Queensland, the Ukraine war (pushing up fertiliser prices) and even herd rebuilding by meat producers – the latter affected by favourable weather.

And other countries are also experiencing higher inflation rates?

Yes. In fact, inflation rates are actually even higher overseas. In New Zealand, inflation stands at 6.9 per cent – a 30-year high. And in the US, the headline rate of inflation stands at a 40-year high of 8.5 per cent.

So if inflation is rising across the globe what can the Reserve Bank do?

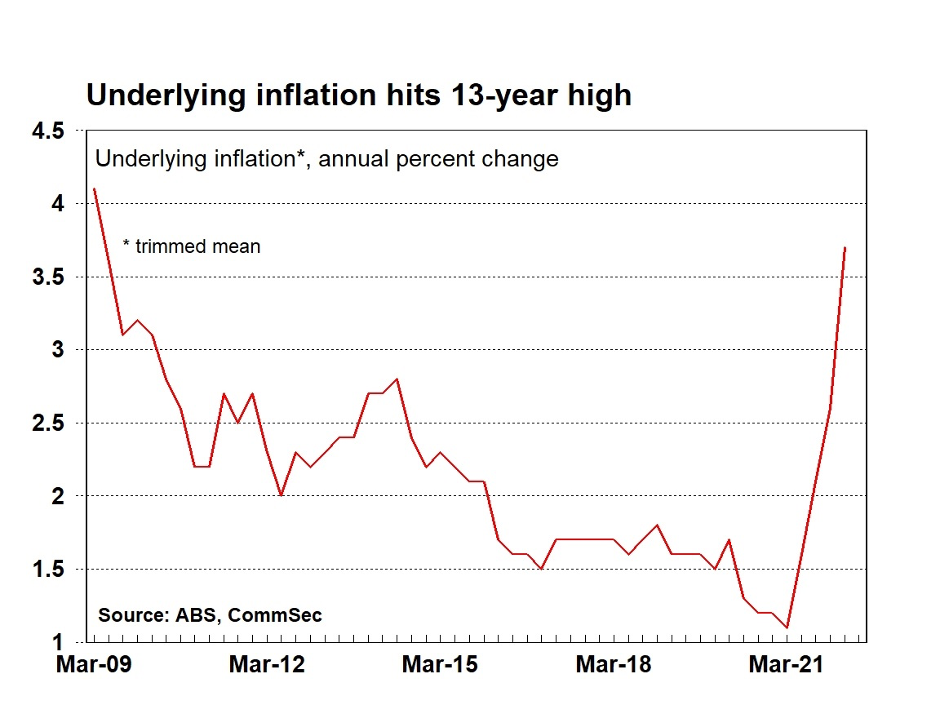

- The Reserve Bank’s (RBA) goal is to keep the annual inflation rate between 2-3 per cent. Clearly, the target is being over-shot at present. That is even the case if you look at the so-called ‘underlying’ rate of inflation (the trimmed mean measure). Stripping out the volatile influences, the annual underlying inflation rate stands at a 13-year high of 3.7 per cent.

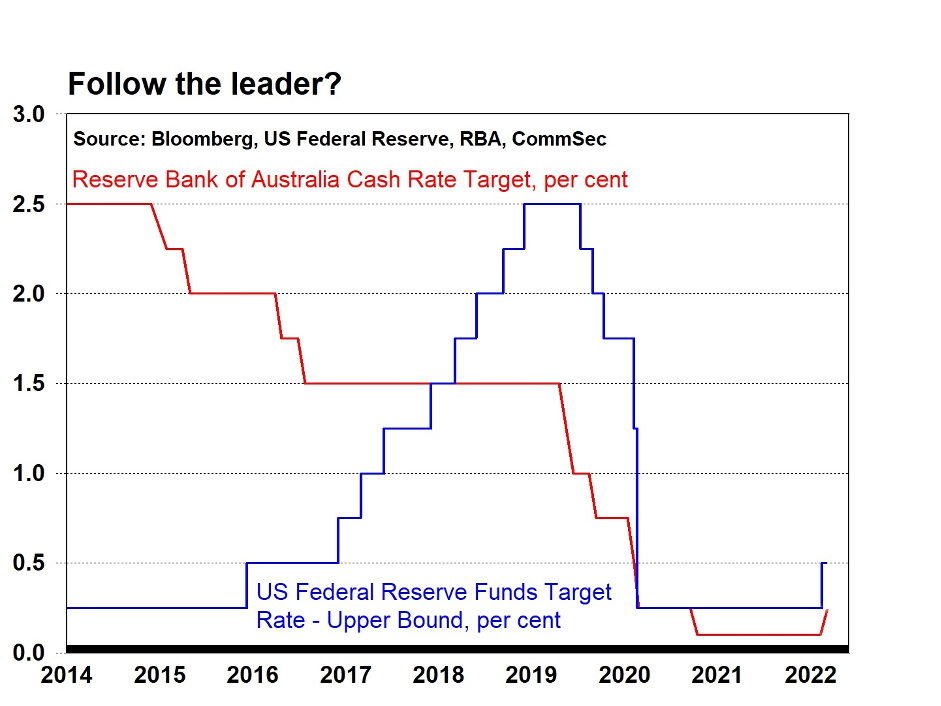

- Now the RBA adjusts interest rates (the cash rate) with the aim of keeping underlying inflation in the 2-3 per cent target band. So with inflation high, the risk is that the Reserve Bank needs to respond by lifting rates aggressively.

- But it is not as simple as that. The Reserve Bank (RBA) can’t do much about high fuel prices and the impact of Covid on the costs of goods (supply-chain issues). And the RBA has to take into account that the Ukraine war may end at some point and that supply-chain problems will recede.

- So while inflation is high at present, that could change if Covid cases continue to fall and the war ends.

So will the RBA lift interest rates?

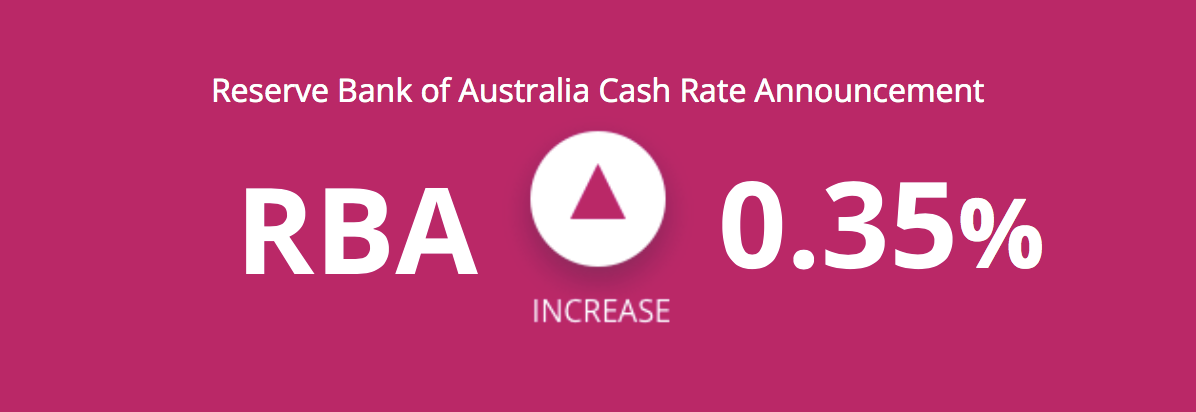

Yes, we expect that the RBA will continue to lift rates over the short to medium term. While the RBA can’t influence world fuel prices and supply-chain issues, it can influence the pace of the Australian economy. A modest lift in interest rates can dampen economic activity and, therefore inflationary pressures. With the economy in solid shape and the job market tight, there is no need to keep the official cash rate at record low levels (As of 3 May 22, it is at 0.35%). Current super-stimulatory monetary policy settings (interest rates) have outlived their usefulness.

When will rates rise and by how much?

- This is the tricky part. The RBA has indicated that it will lift rates when it is confident that the underlying rate can sustainably be maintained between 2-3 per cent. The sharp lift in the inflation rate will give the RBA confidence that the target will be achieved.

- But the RBA has also indicated that it will lift rates when there is evidence that wages are again growing at a 3 per cent annual rate or higher. The problem is that the key data on wages – the wage price index – is not released until May 18. In addition, the federal election is held on May 21, and the national accounts – a report that contains economic growth and wage data – is released on June 7.

- So while the rate was increased by 25 basis points to 0.35% on Tuesday (May 3), it is possible the RBA might lift rates again at the June 7 Board meeting.

- The bottom line, rates are likely to rise; it’s just the timing and the size of the move that need to be decided.

Does the election affect the timing of rate hikes?

- The Reserve Bank says it doesn’t. But in practice, if you were the Reserve Bank Governor, would you lift rates in an election period?

- If there were a clear case for higher rates, then the Reserve Bank wouldn’t delay. It would lift rates at the first opportunity. But presumably, the Reserve Bank doesn’t have its answer yet on what is happening with wages. Unless its business liaison programme has found clear evidence of a solid lift in wages.

- The Reserve Bank Board made its position clear at the last Board meeting: “Members also noted that, for some time, the Board had been communicating that it wanted to see evidence that inflation is sustainably within the 2 to 3 per cent target range before increasing interest rates. It had also been communicating that this was likely to require a faster rate of wages growth than had been experienced over previous years.”

- When it comes to rate decisions, the Reserve Bank says that the fundamental question posed is: of all decisions that could be made, which decision would I regret the least?

And by how much are rates expected to rise?

- The cash rate currently stands at 0.35 per cent or 35 basis points. Traditionally the RBA has preferred to move in increments of 25 basis points. So future moves will likely be in 25 basis point multiples.

- Economists are debating all the permutations and combinations.

- Of course, there is no reason why cash rates move in 0.25 percentage point increments – it’s just what has happened in the past.

- It is also important to note that before the 3 May increase, the last time the cash rate was increased was 11½ years prior, in November 2010.

How much have rates risen in other countries?

There are a few examples. Reserve Bank New Zealand has lifted rates four times – the last move by 50 basis points – taking the cash rate to 1.50 per cent. The US Federal Reserve has raised rates by 25 basis points and is tipped to lift rates by 50 basis points next Wednesday to 0.75-1.00 per cent. And the Bank of England has lifted its primary Bank Rate three times to 0.75 per cent. In each case, inflation is higher than in Australia.

How high can rates go in Australia?

- There is no pre-determined timetable for rate hikes or an interest rate goal. And there are a lot of factors to be considered, including wages, prices, unemployment, the fabled ‘full employment’ level, population growth and economic activity.

- Commonwealth Bank Group economists expect the cash rate to be lifted gradually over the coming year, with the cash rate coming to rest at a ‘neutral’ level of 1.25 per cent. The neutral rate is a rate that is neither acting to speed up the economy nor slow it down.

- With consumers carrying higher debt levels than in the past, small changes in rates can significantly impact spending, borrowing, and overall economic activity.

So bad news for borrowers?

- A lift in the cash rate affects a raft of both loan and deposit rates. A rate hike could mean higher borrowing costs for variable-rate loans. New borrowers are directly affected but for existing borrowers, much depends on whether they are paying more than they need to in loan repayments.

- The Reserve Bank Board has noted that “in households with an owner-occupier variable rate mortgage, the median excess payment buffer had increased to an equivalent of 21 months of required payments, up from 10 months at the beginning of the pandemic.”

- Of course, some groups in the economy will be cheering on rate increases. Namely depositors. Included in this group are those saving to buy a home, those who rent and older Australians such as those on an old-age pension and self-funded retirees.

- Around two-thirds of households either own their home outright or are renting.

What are other issues to consider when considering interest rates and inflation?

- One issue is inflation expectations. If consumers and businesses believe that inflation will stay at 5 per cent, it could factor that into business and investment decisions. Voilà, instead of 2-3 per cent, inflation gets locked in closer to 5 per cent. The Reserve Bank has to be careful that it doesn’t take too long to address higher rates on inflation.

- This leads to a second issue, something called ‘jawboning’. Monetary policy is not just what the Reserve Bank does with interest rates; it’s what it says in terms of guidance. Consumers and businesses need to be clear that the Reserve Bank is committed to the 2-3 per cent target band and will do what it takes to achieve the goal.

What does this mean for investment markets?

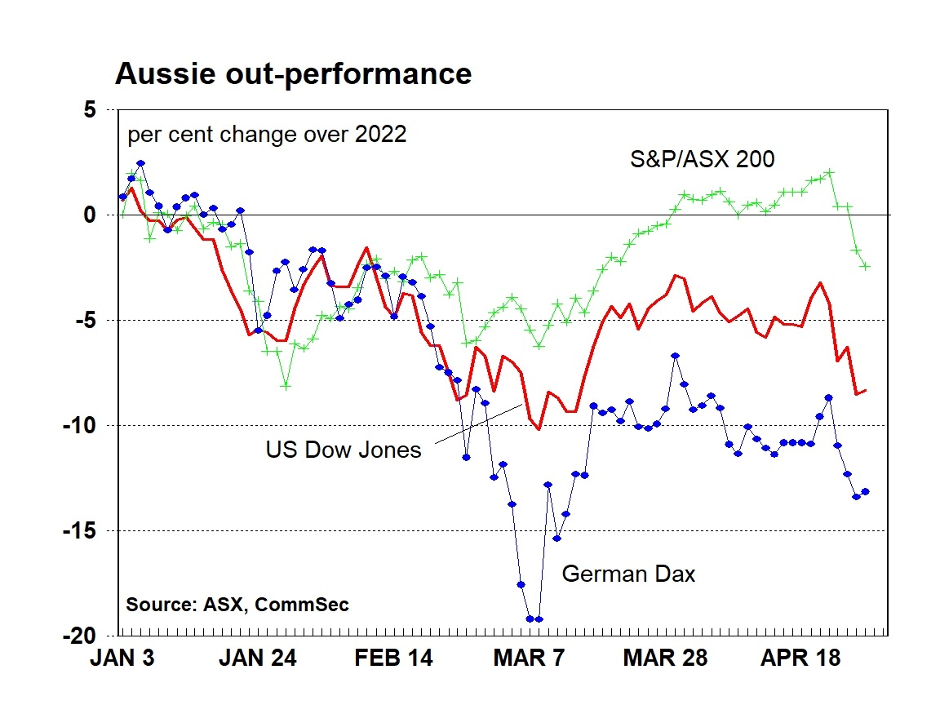

- Central banks lift interest rates when economies are doing well and expecting to keep doing well. And not just doing well, a little too well. In Australia, the Reserve Bank wants to run the economy at the fastest possible rate that is consistent with inflation holding between 2-3 per cent. The RBA want to ensure that all people that want to work, can work. And that workers receive wage increases that are consistent with productivity. In other words a good job, for a good rate of pay.

- Central banks don’t always get this right. They might lift rates too far or too fast and that could cause the economy to slow too much.

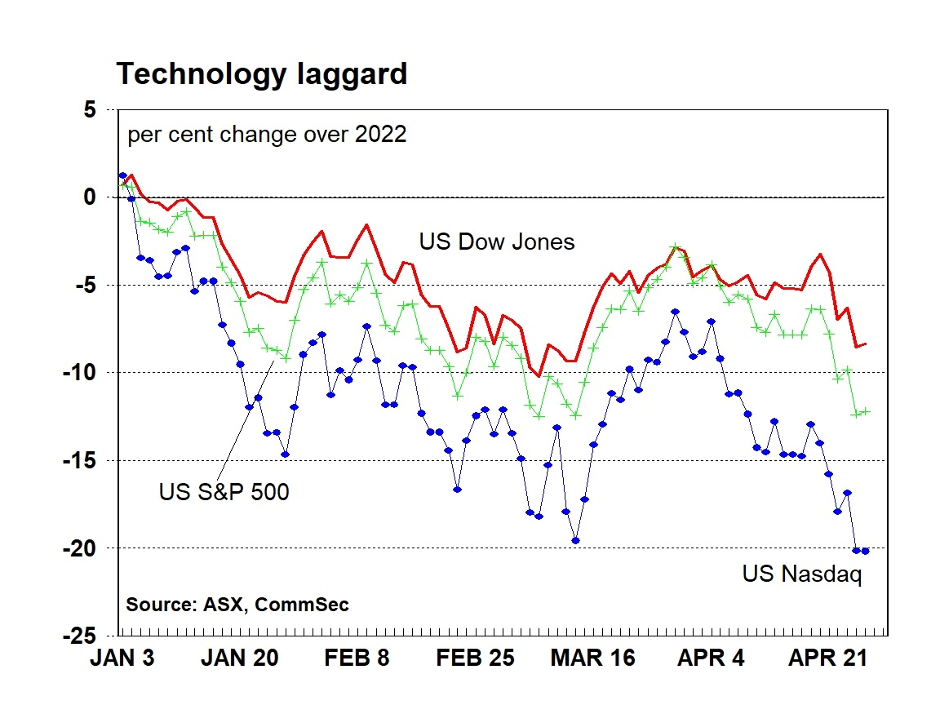

- That has been a key concern in the US over 2022. The job market is tight and wages and prices are running at a fast clip. Policymakers may respond next week by lifting rates by 50 basis points or 0.5 percentage points. For companies that rely on the economy to grow at a solid rate to support revenue growth – companies like technology firms and upmarket retailers – that is a concern.

- However once it’s clear that the economy is still growing, and at a slower but sustainable pace, growth-focussed companies breathe a sigh of relief. And overall, investors become confident again to put funds to work in the sharemarket as opposed to cash or fixed income markets.

- At the early stage of a period of rising interest rates, banks and defensive sectors like consumer staples, utilities and health care tend to be favoured over technology and consumer discretionary sectors of the sharemarket.

- Real estate prices are also expected show slower growth, stall or go backwards when rates are rising.

We are here to help

As with everything, If you need any assistance with your situation, please contact our Client Care Team on (08) 9227 6300 or via our Contact Us Page for more information.